Bloom, Indoor Composter & Garden

Bloom reimagines urban composting at the household level, aiming to make it more engaging and accessible, while transforming nutrient-rich waste into a valuable resource.

Around one-third of global food production is wasted each year, much of it at the consumer level. Items like coffee grounds, eggshells, and vegetable scraps, which contain nutrients ideal for enriching soil, often end up in landfills where they decompose without oxygen, producing methane, a harmful greenhouse gas.

Traditionally, composting requires outdoor space, making it challenging for urban dwellers. Indoor composting setups are often makeshift and hard to maintain, lacking appeal. Bloom explores highlighting the ~magic~ of composting and visualizing the benefits of extracting nutrients to feed back into a garden system, creating a more interactive way to repurpose household waste.

Around one-third of global food production is wasted each year, much of it at the consumer level. Items like coffee grounds, eggshells, and vegetable scraps, which contain nutrients ideal for enriching soil, often end up in landfills where they decompose without oxygen, producing methane, a harmful greenhouse gas.

Traditionally, composting requires outdoor space, making it challenging for urban dwellers. Indoor composting setups are often makeshift and hard to maintain, lacking appeal. Bloom explores highlighting the ~magic~ of composting and visualizing the benefits of extracting nutrients to feed back into a garden system, creating a more interactive way to repurpose household waste.

Turning waste into an opportunity. A speculative deep dive exploration on

engaging with waste as it’s generated to promote more mindful consumption.

6 weeks

Course: Designing for Complex Product Systems

Industrial Design, Systems Design,

Rapid Prototyping, Solidworks, Keyshot

6 weeks

Course: Designing for Complex Product Systems

Industrial Design, Systems Design,

Rapid Prototyping, Solidworks, Keyshot

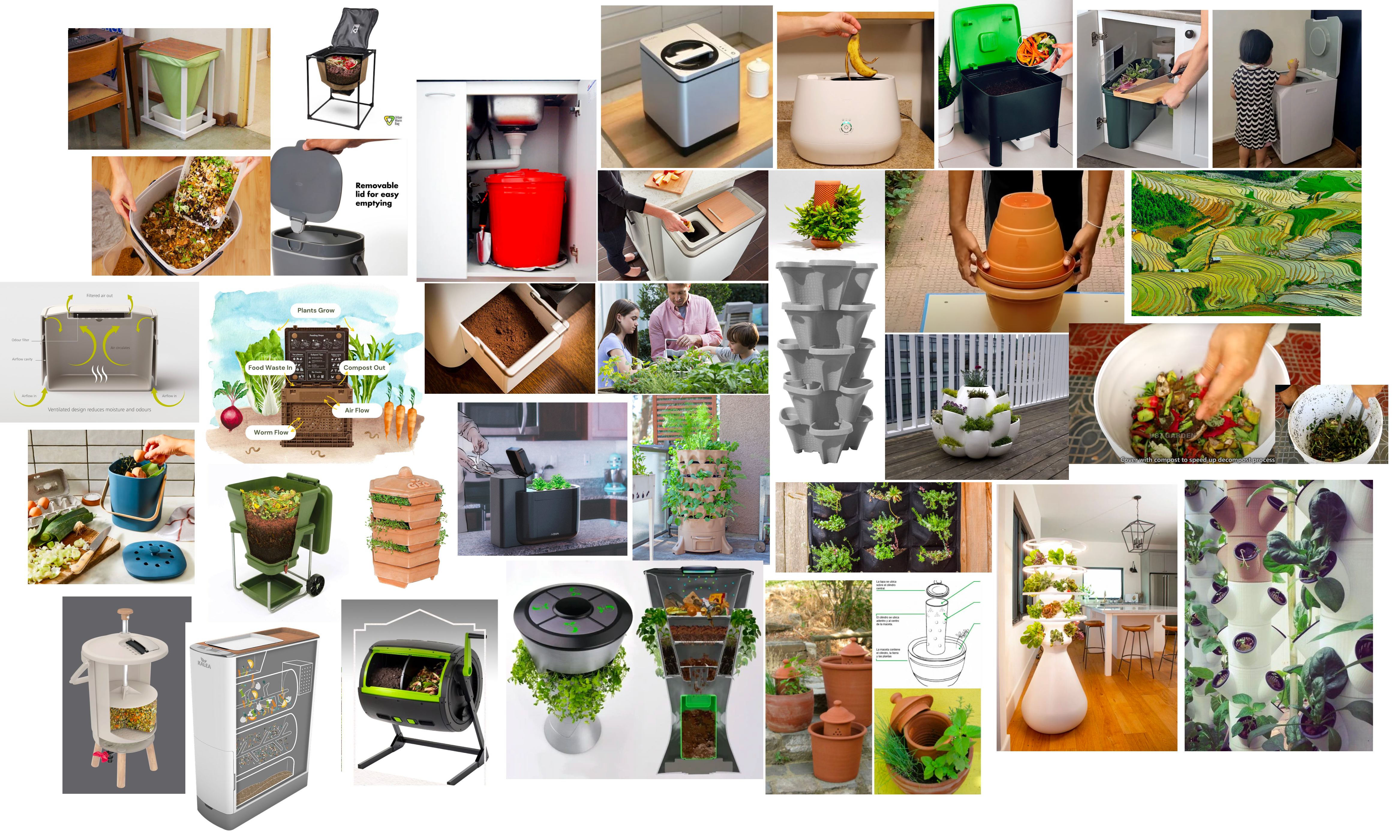

What solutions exist?

Many current indoor composting systems leave people dissatisfied. High-tech options like Mill and Lomi consume substantial energy and even encourage shipping compost back to the manufacturer which is helpful but can feel counter-intuitive. Dustbin-style containers act as collection points for community bins, but the speration to what happens to the waste reduces motivation or any personal pride related to the process.

This led me to explore how a composting system could be designed to keep families engaged throughout the cycle, making the process more productive and rewarding.

Personal testing

This project began with my own desire to be more mindful of the waste I generate. I decided to try a small composting setup with my roommates to observe the process and identify pain points firsthand.

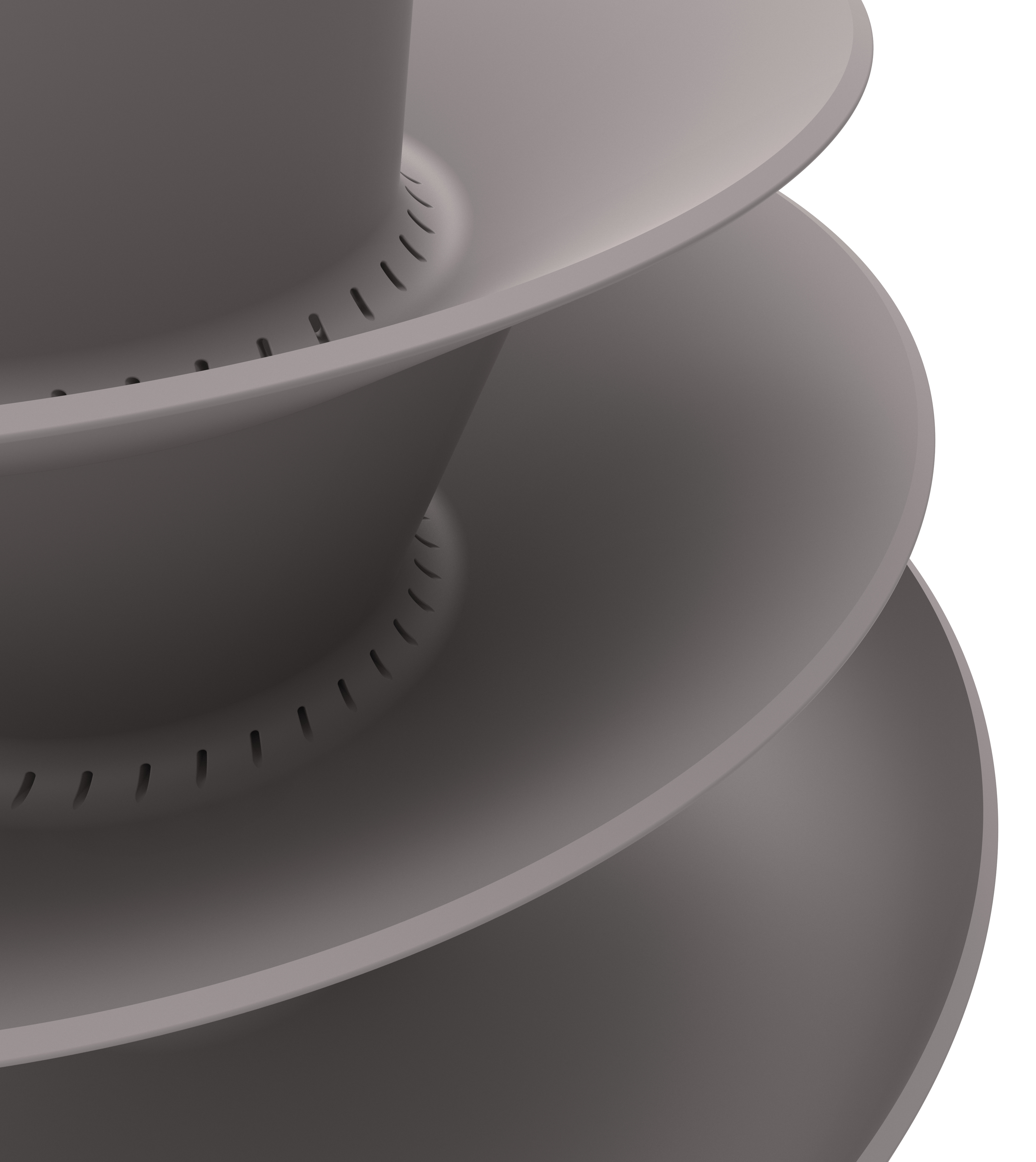

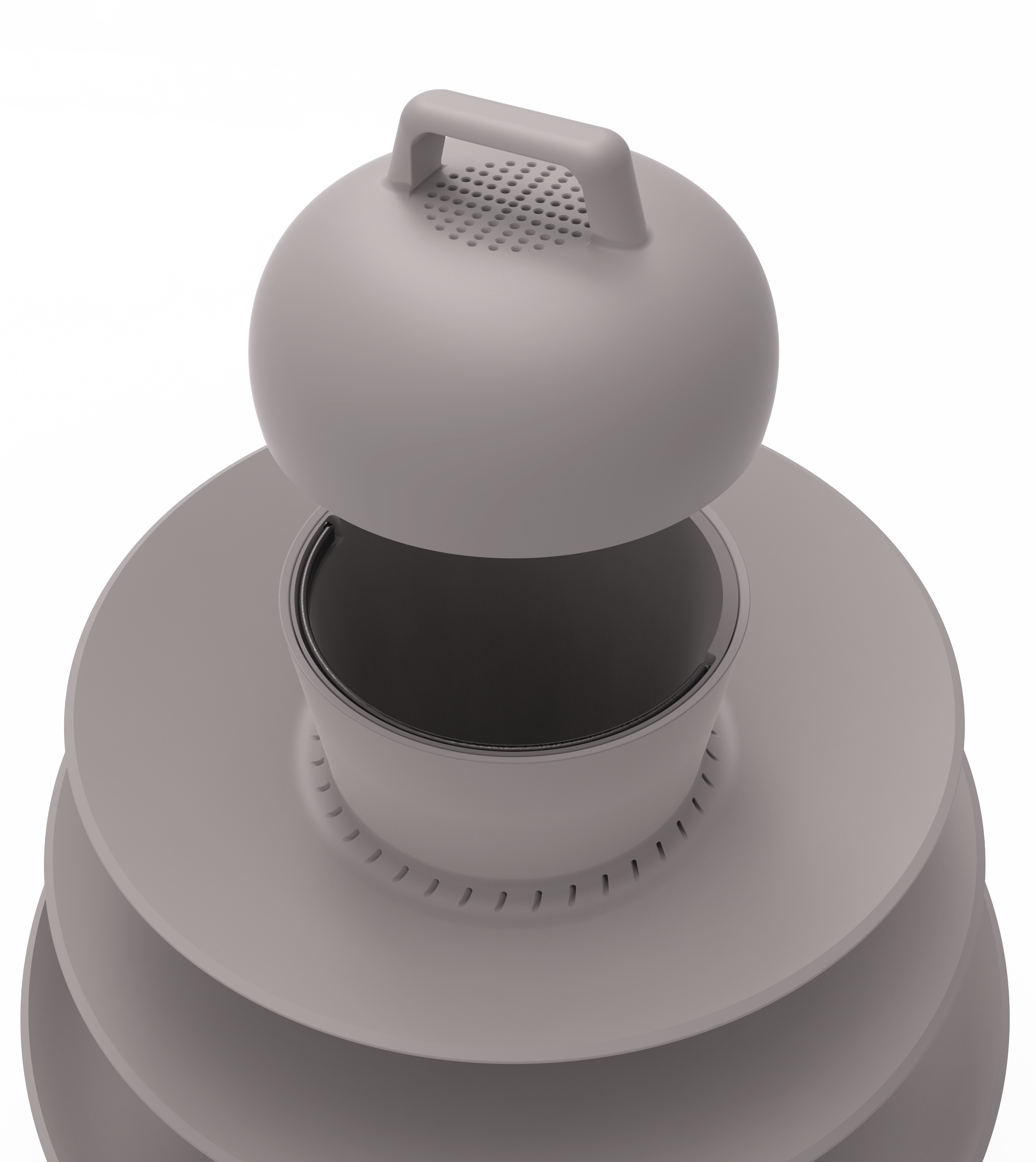

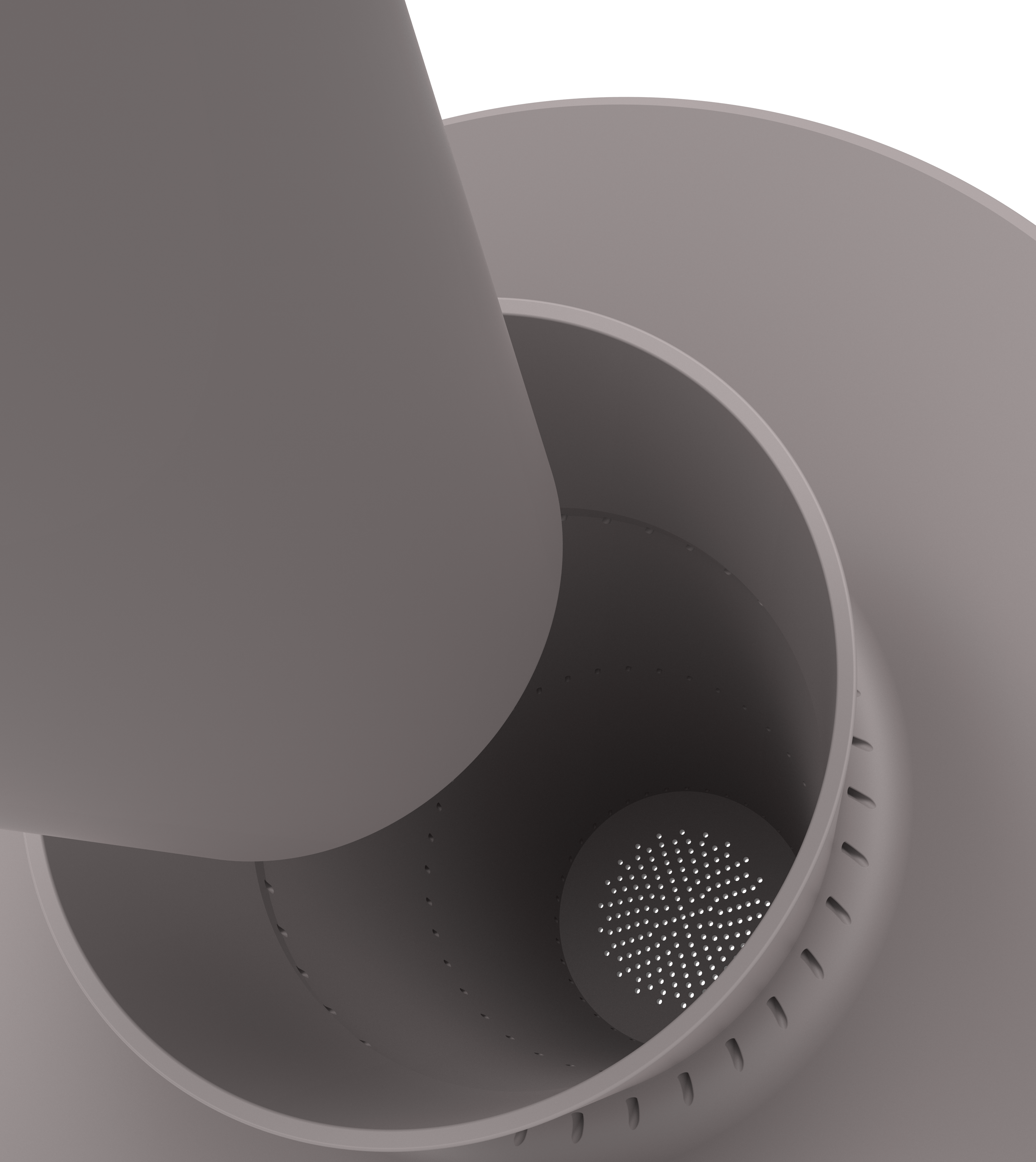

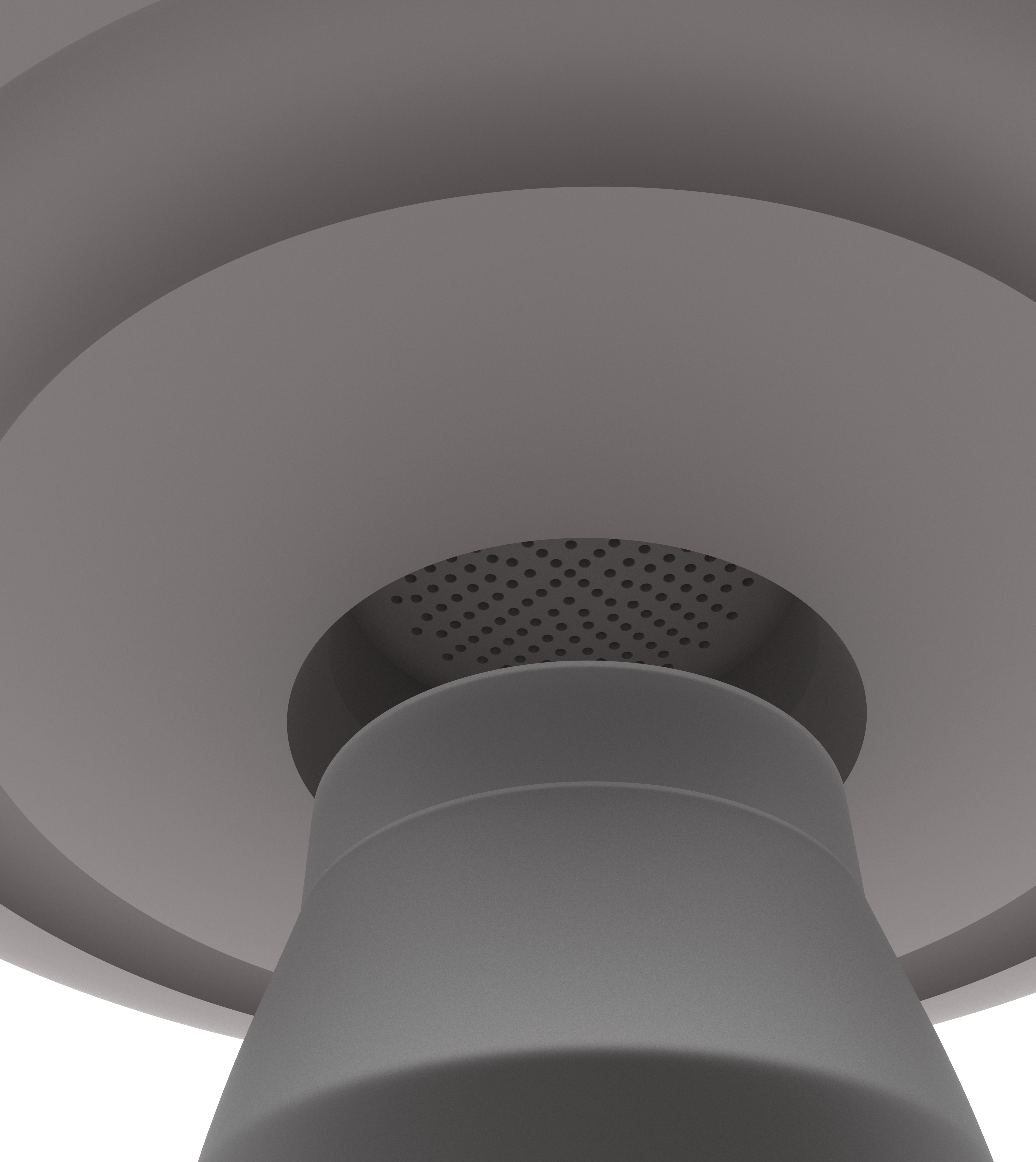

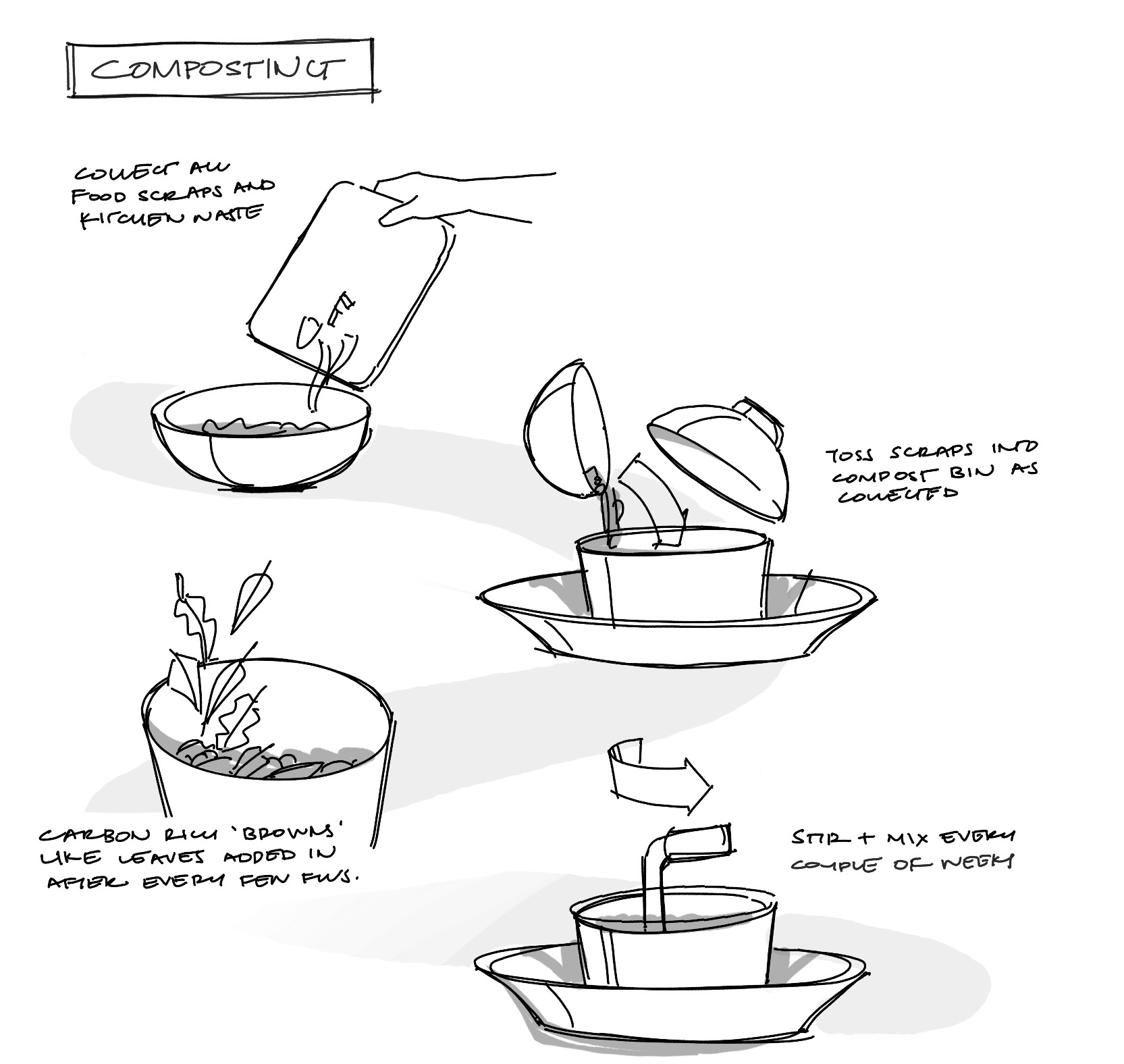

With advice from a friend and some research, I started using a deli container to collect coffee grounds, fruit and vegetable peels, old produce, and eggshells, balanced with dry leaves gathered outside. The setup worked well, but I quickly learned the importance of managing moisture levels. Initially, I hadn’t added enough holes in the container lid for proper air circulation, which led to excess moisture and odor. Adding more holes resolved this and is a feature I incorporated into the composter’s design. Balancing moisture by adding “browns”—carbon-rich materials like dry leaves or shredded newspaper—also helped reduce odors and is an easy tip for other households.

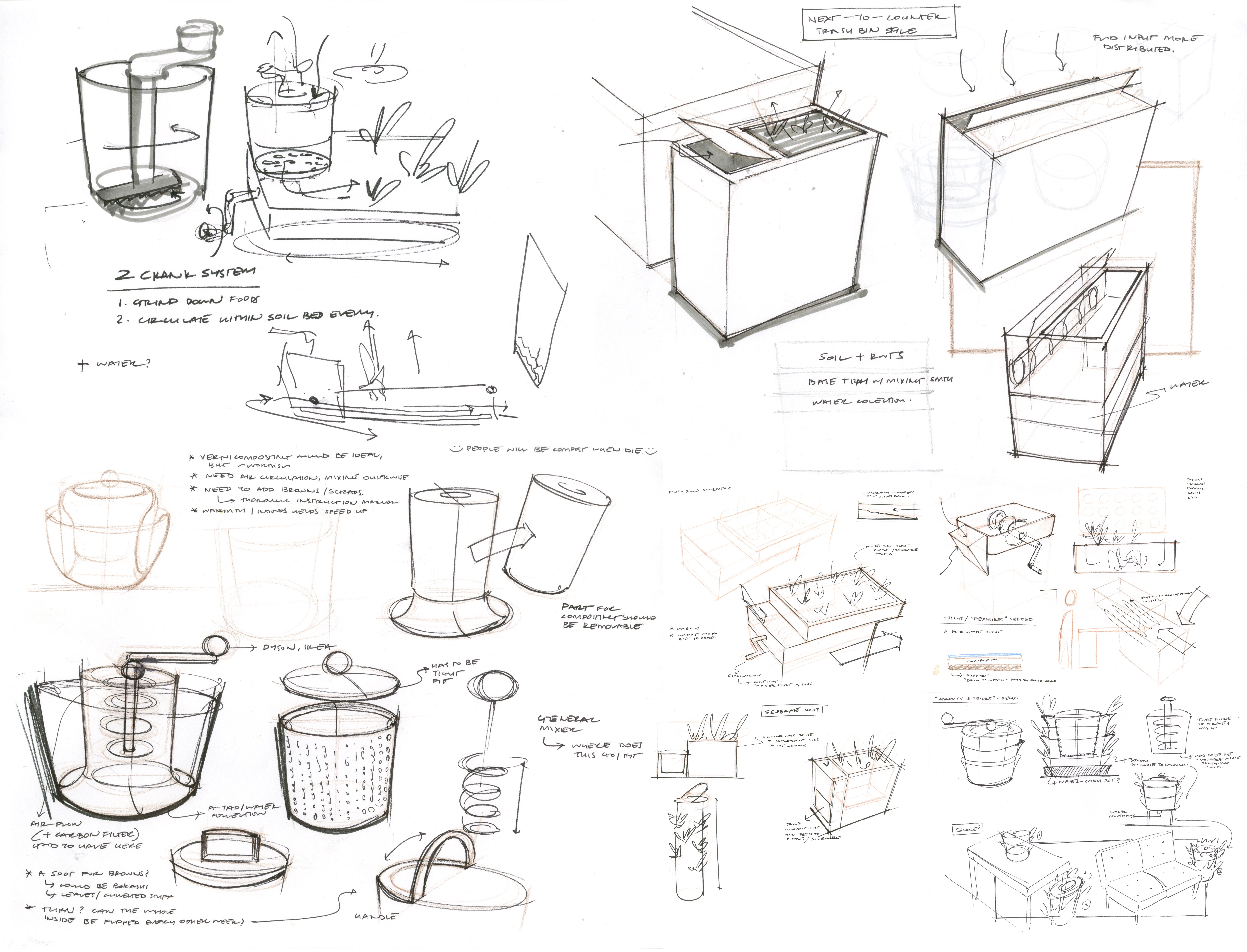

Initial Ideation

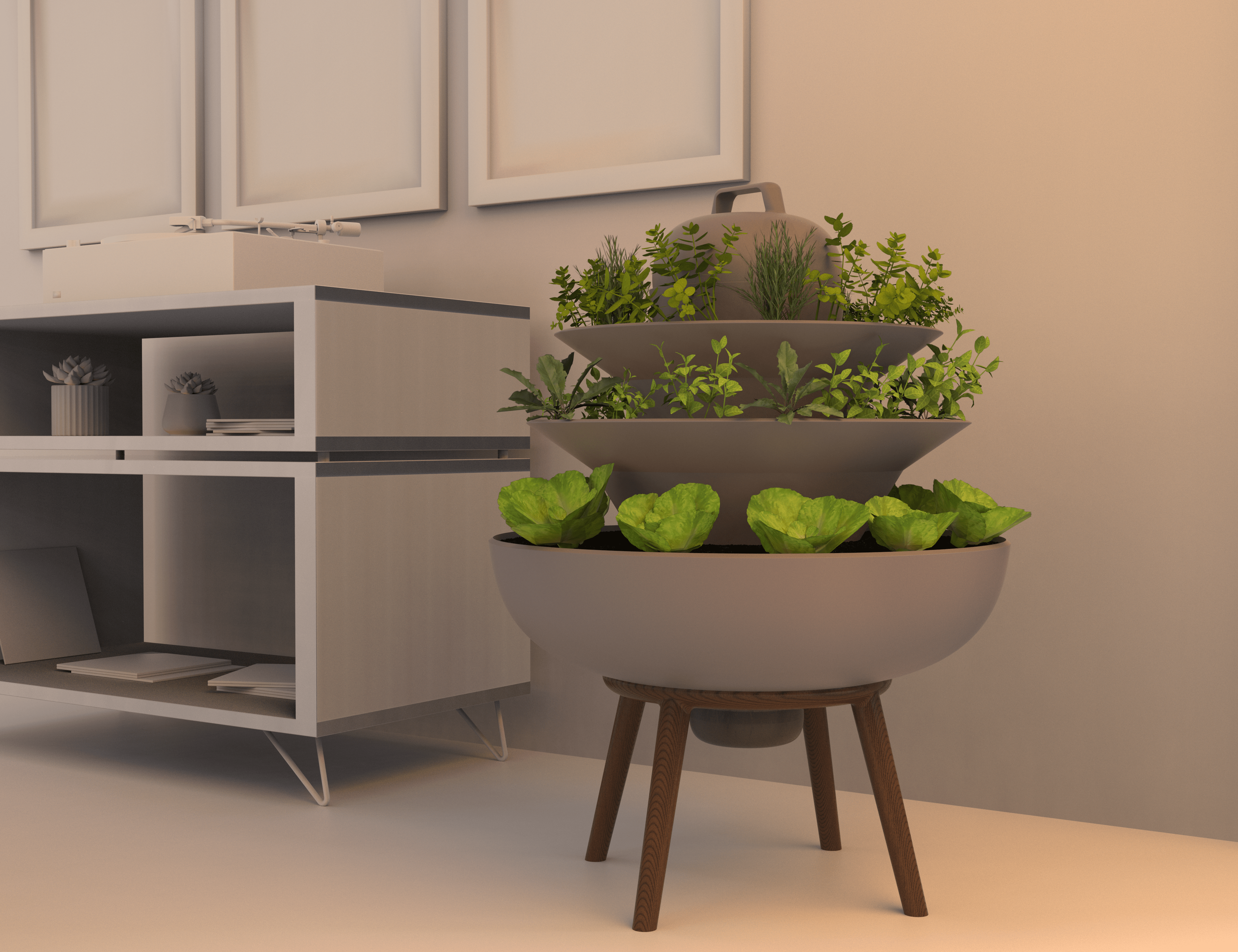

I wanted the composter to focus on an urban gardening aspect and fit in like furniture in a home. Another priority was ease turning the waste which can to be done every 1- 2 weeks to aerate the material, and a collection system for excess moisture ideally for both the compost and garden.

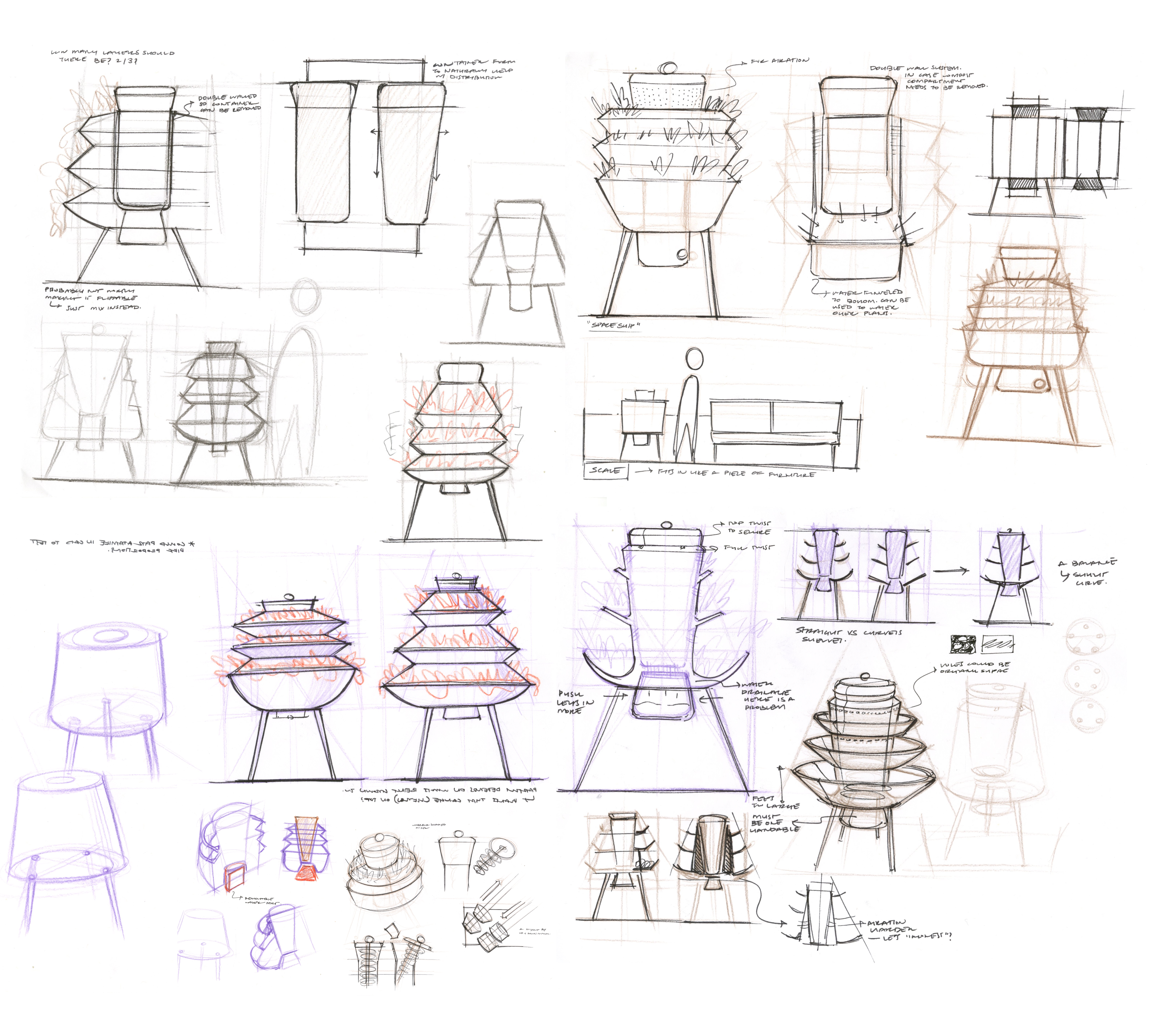

Refining form and scale

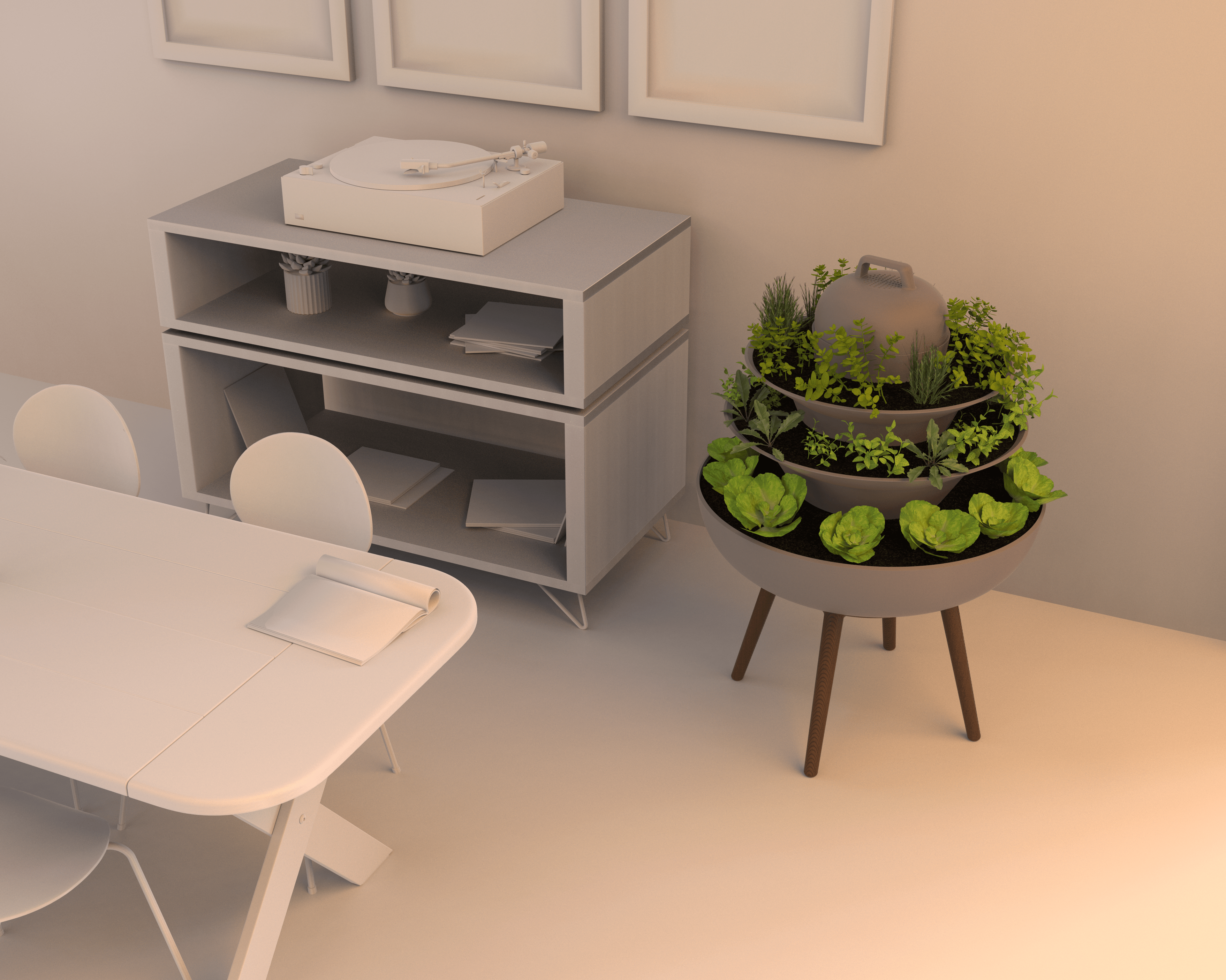

It became apparent early on that for this to become an engaging home ritual and effectively complete the composting cycle, the composter-planter would need to be of a slightly larger scale—more akin to a side table than a tabletop appliance.

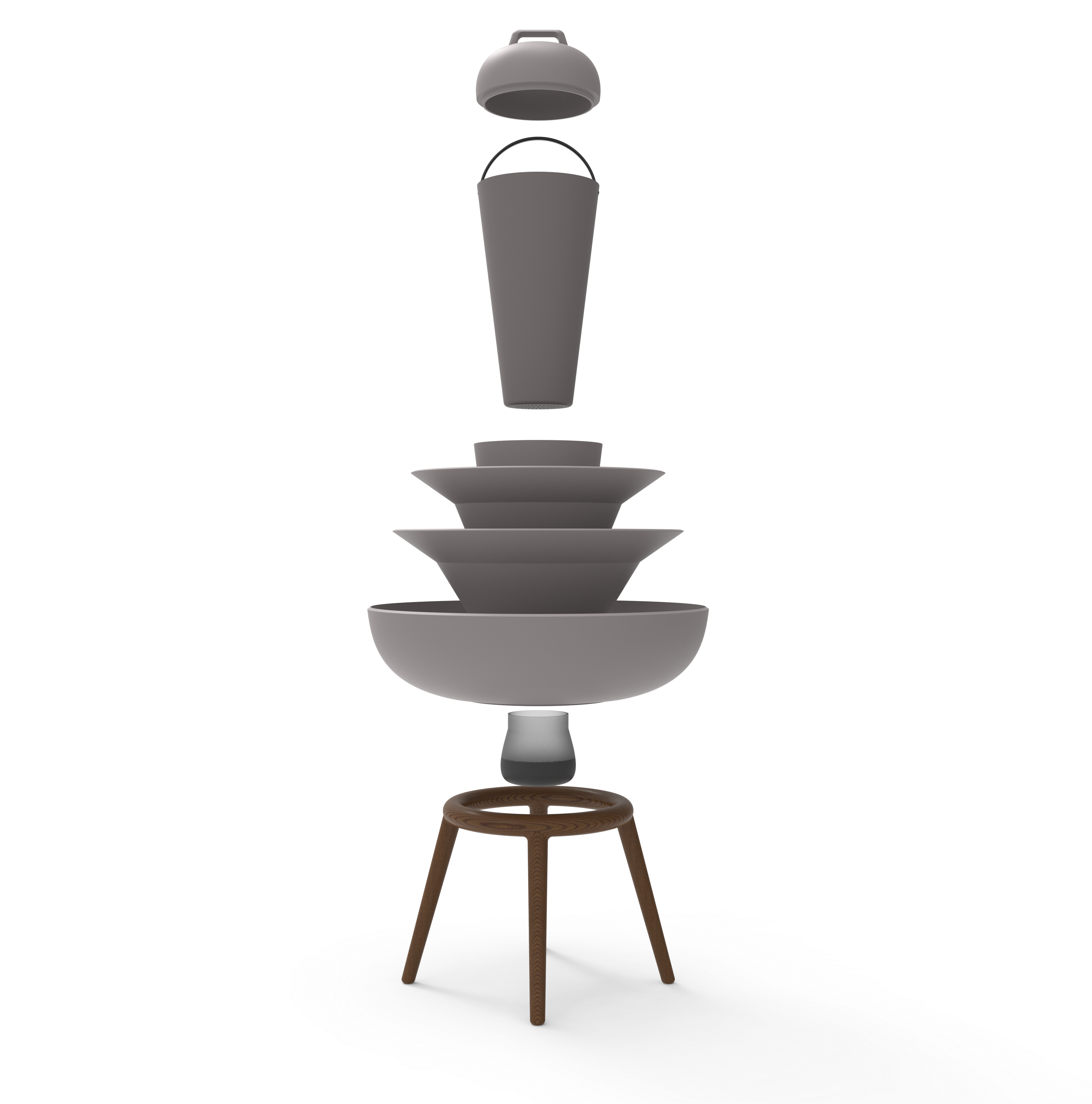

Leveraging height would enable a larger bin and provide more space for growing larger vegetables such as lettuce in a smaller apartment. I settled on a pagoda-spaceship-like 3-tier system that efficiently separates space for growing different-sized foods while embracing the compost bin in the middle.

Physical Prototyping

3D printing scaled down models allowed me to view and understand the object in physical space.

It feels a bit ironic to be proposing something that will require the use of valuable resources and materials for its manufacturing, processing and transport to lower the impact the a human will have on the environment. At the same time, ideally this would be an object that people are excited to engage with for a long time and integrates well into their space so it’s beneficial for the materials and processes to be of good quality, however, this would also raise the costs, making it inaccessible to a lot more people.

This balance between upfront costs and long term benefits from habit forming has been a struggle throughout this project, and one I haven’t figured out yet, so much is currently speculation. I’d like to imagine compost-garden designs that are open source and designed to be made with common or found materials.

This balance between upfront costs and long term benefits from habit forming has been a struggle throughout this project, and one I haven’t figured out yet, so much is currently speculation. I’d like to imagine compost-garden designs that are open source and designed to be made with common or found materials.